8 questions before estimating the detection range of a signal of interest

Estimating how far away a signal can be detected sounds like it should be straightforward. Yet, in practice, every signal, every environment, and every receiver behaves differently. Signal strength, antenna gain, atmospheric absorption, terrain, and interference all play a part, and that’s before we account for deliberate jamming or low-probability-of-detection techniques.

In an increasingly congested and contested spectrum, it’s no longer enough to make simple “rule-of-thumb” assumptions about detection range. Operators need accurate, data-driven estimates that consider real-world conditions, and tools that can model, visualise, and optimise sensor deployments before any equipment is fielded.

This article explores the main factors affecting detection range and highlights eight key questions to ask before estimating how far a signal of interest can be detected. It also shows how RFeye hardware and software help users overcome these challenges by combining precise sensing with advanced modelling and analysis.

Factors affecting detection range

Radio Frequency (RF) propagation follows the inverse square law: received power decreases with the square of the distance from the transmitter. If you know the transmitted power and receiver sensitivity, you can estimate the maximum distance before a signal becomes undetectable.

However, this assumes ideal “free-space” conditions, which rarely exists in reality. Terrain, foliage, atmospheric effects, reflections, and interference can all attenuate or distort a signal, while equipment characteristics such as antenna gain, receiver noise figure, and processing capability also determine how far a signal can be detected.

A more complete view comes from the Friis transmission equation, which shows that received power:

- Decreases with the square of the distance from the transmitter

- Decreases with the square of the wavelength

- Increases with the gain of the transmitting and receiving antennas

- Increases with the power of the transmitted RF signal

Friis represents the best-case scenario. Real-world propagation requires more advanced models that account for ground reflections, obstacles, and atmospheric conditions.

This is where the simulation tool in RFeye Site become invaluable, which allows users to model these variables across real terrain data, helping predict where a signal can and cannot be detected and how sensor placement can be optimised to achieve maximum coverage.

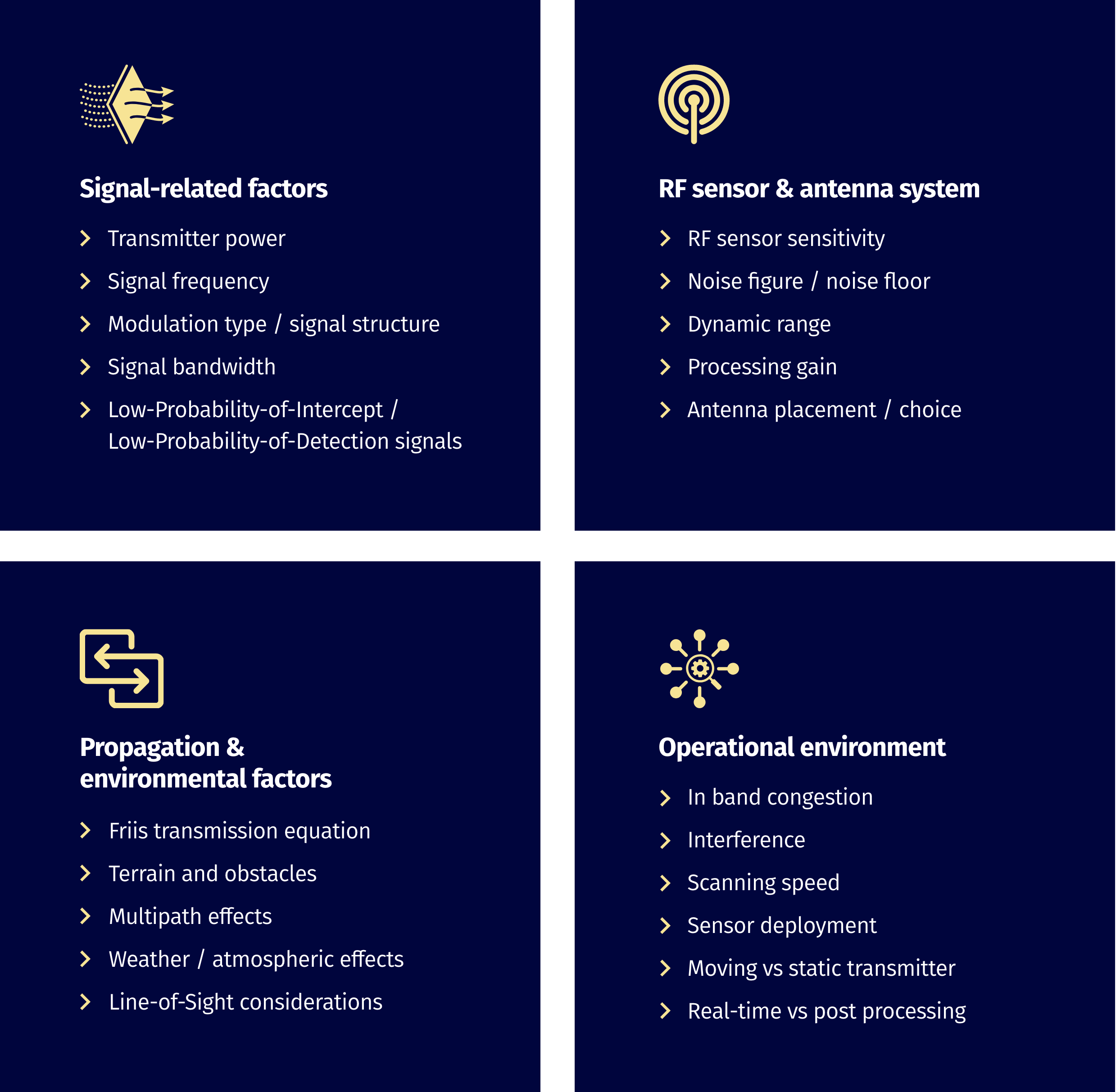

Figure 1: Factors that affect the maximum detection range for an RF signal

Question 1: What is the power of the signal I am trying to detect?

Transmitted power fundamentally determines how far a signal can travel before dropping below a receiver’s noise floor. According to the inverse square law and the Friis equation, higher power means longer potential range, but only up to a point.

Increasing transmit power is often constrained by regulatory limits, platform capability, or the need for low-probability-of-intercept (LPI) operation. In these cases, improving receiver sensitivity or antenna gain is more effective than boosting transmit power.

RFeye Nodes provide exceptionally low noise floors and wide instantaneous bandwidths, allowing users to detect weak signals over greater distances. When combined with directional or higher-gain antennas, these sensors can extend detection range without altering the transmitter itself.

Question 2: How congested is the spectrum in that band?

RF transmissions must stay within certain allocated bands of the spectrum. However, the increased number of wireless devices has led to overcrowding in popular bands. This means that the transmitted signal must compete with other signals in the same band and this can lead to RF interference, signal degradation, and reduction in range.

A site assessment can determine the level of interference a signal will experience. This measurement can be done before transmission to get a base level but can also be done throughout the transmission to actively monitor the level of interference.

To limit the impact on the signal, it may be possible to remove the sources causing this interference or to use signal processing techniques to recover a partial or faint signal. It may also be possible to change the frequency of the signal: normally this means increasing the frequency, as currently higher frequency bands tend to be less congested. Whether this is a possibility for the signal in question will be discussed in the next question.

Question 3: What frequency band is the signal in?

Frequency has a direct impact on propagation and range. Lower frequencies travel farther and diffract more easily around obstacles, while higher frequencies offer wider bandwidths but are more susceptible to absorption and scattering.

Choosing the right frequency is therefore a trade-off between range, bandwidth, and interference. Lower bands (VHF/UHF) may be saturated but provide longer reach; higher bands (C-band, X-band, Ku-band) offer cleaner spectrum but shorter propagation paths and higher equipment costs.

The RFeye Nodes are wideband sensors, from 9KHz to 40GHz, allowing operators to detect and analyse signals across the full spectrum without hardware changes.

Question 4: What kind of terrain and obstacles are between me and the transmitter?

Theoretical models assume clear line-of-sight propagation. In practice, hills, buildings, trees, and other obstructions can cause multipath effects, which can drastically reduce detection range or create multipath interference.

A site survey can preempt these losses, but software simulation is easier. Using RFeye Site, users can perform propagation analysis across real terrain datasets, analyzing how a signal travels across forests, over bodies of water, and through urban areas. The software helps determine the most effective sensor placement for line-of-sight or non-line-of-sight detection.

Even when obstacles cannot be removed, range can be extended by elevating antennas, adjusting receiver placement, or increasing the number of sensors to triangulate weaker reflected signals. Moreover, post processing software can be used to distinguish between the multi-path signals therefore increasing the chances of the information in a signal being received.

Question 5: What sensor, network, and antenna setup am I using, and where are they deployed?

Receiver sensitivity and antenna gain are critical determinants of how far a signal can be detected. A high-gain, directional antenna can extend range dramatically by focusing on a smaller spatial area, while an omnidirectional antenna provides broader coverage at reduced sensitivity.

RFeye Nodes and RFeye Arrays have a low noise figure and wide dynamic range, enabling accurate detection of weak or intermittent signals. Modular antenna options allow users to tailor gain and beamwidth to mission requirements.

Deployment geometry also matters. Placing a network of sensors on elevated structures or tethered UAVs can enhance line-of-sight.

Question 6: What is the sensitivity and noise figure of my sensor?

The choice of sensor determines the strength of the signal that the receiver network can detect. The more sensitive the sensor, the weaker the signal it can detect. This is achieved through a combination of the sensitivity and the noise figure of the receiver.

To be able to detect a signal, it generally must be stronger than the noise floor of the receiver as this makes the signal indistinguishable from background noise and interference levels. To overcome this limitation, it is possible to use a software modulation scheme in certain situations.

Question 7: Do I need to detect the signal in real-time or in post-processing?

If the signal can be detected in post-processing, it is possible to use more complex and time-consuming software processing tools to detect your signal. This allows you to detect weaker signals, particularly if you can integrate the signal over time. If real-time processing is required, this limits the choice of techniques and therefore limits the distance the signal can travel.

It is also worth considering how a signal needs to be detected—do you only need to detect the existence of a signal, or to decode and demodulate it to extract the data? As the requirements increase, the signal strength must also increase to limit data corruption.

Question 8: What detection technique am I using, and what processing gain can I achieve?

RF signals are detected by an antenna and sensor network; how these are set up depends on what you are trying to detect. A single receiver can be used to detect the existence of a signal; however, if something more sophisticated like signal geolocation is required, then at least three receivers will need to be deployed, allowing the highly accurate Time Difference of Arrival (TDoA) methodology to be used. The location of each receiver needs to be calculated to ensure that the signal can be detected. This can be achieved with a comprehensive site survey and depends on the receiver units installed.

The processing gain of a sensor indicates how well it can distinguish a signal from the noise. This is commonly done using a technique called spread spectrum, where the narrow band information of a signal is modulated over a wider frequency bandwidth. Clearly a high processing gain is preferred and can be achieved with the correct hardware and software.

Conclusion

There is no single answer to “how far can I detect a signal?” Every case depends on transmitter power, frequency, environment, hardware sensitivity, and processing approach. What matters is the ability to understand, model, and optimise all these factors together.

The RFeye ecosystem gives operators that capability. Its high-performance hardware extends detection range through superior sensitivity and dynamic range, while its software tools simulate how signals behave across real terrain.

Brochures & guides

RF simulation software for RF training

RFeye Site has traditionally empowered spectrum managers to identify and geolocate signals of interest emitted in or around an RFeye Node network. RFeye Site Simulator provides experienced and trainee spectrum managers with the same capabilities but employs simulated RF sensors. By simulating real-world scenarios, this powerful tool can be used for interference hunting, strategic planning, and spectrum allocation.

Tamara Clelford

Dr Tamara Clelford, director of Polynode, is a consultant physicist and writes guest posts for CRFS. She has 20 years of experience in the antenna and RF world both with hands on design, test, analysis and simulation.